Postcards from the General Slocum Disaster Memorial

(Lutheran Cemetery, Middle Village, Queens, New York)

Carol L. Robinson

February 12, 2022

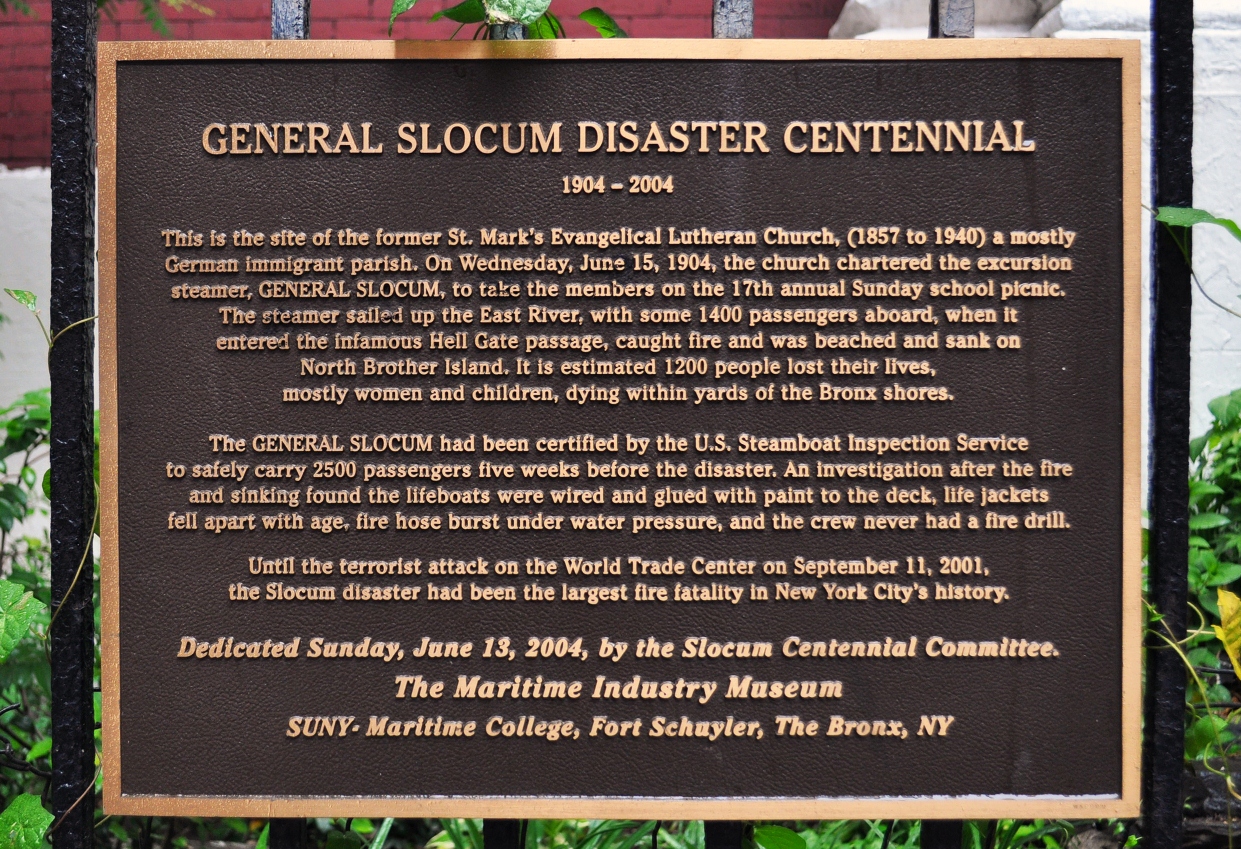

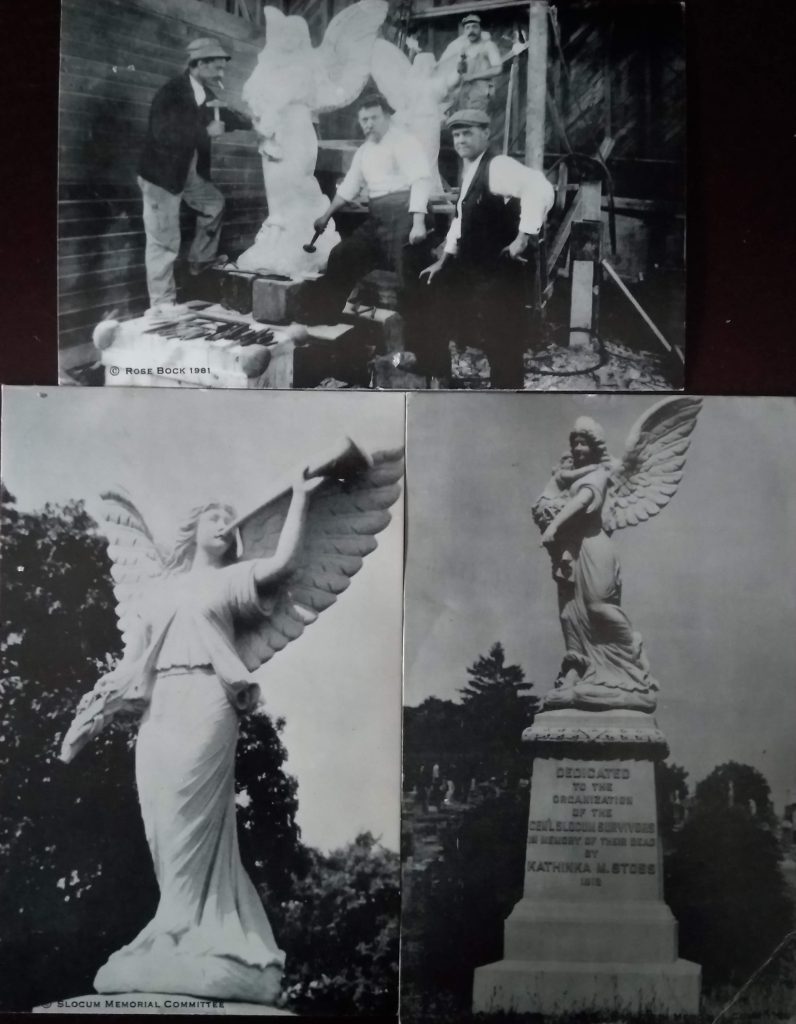

The above pictured statues are a part of the General Slocum Disaster Memorial (located at Lutheran Cemetery in Middle Village, New York; there is also a fountain in Flushing, New York). The Slocum Memorial was created in the early 1900s, in memory of the hundreds of people who died in what is still considered to be “the deadliest disaster in New York before 9/11” (Gilbert King, Smithsonian Magazine.) In 1904, the General Slocum sank and killed over 1,000 people. The memorial was created by several artists. The original memorial was dedicated in 1905. My great grandfather, Adam Bock, was commissioned to create the two angels (pictured above) several years later; they were added in 1912 (Roadside America).

In the top postcard, Adam is the portly elderly man with the beard, and the guy way in the back is his son, my Great Uncle Paul. My Great Aunt Elizabeth (Paul’s younger sister) had to pose, for hours and hours, for the angel holding the trumpet—which she used to laughingly complain about all the time. These two statues are not the main part of the memorial, but they are important to me for nostalgic reasons: looking at them somehow makes me feel closer to my Great Aunt Elizabeth, and I also feel like I might know my great grandfather and great uncle—if only just a little. It’s strange, however: what is a symbol of tragedy to other people is a symbol of pride and heritage to my family.

The General Slocum Disaster Memorial at Lutheran Cemetery, Queens, N.Y. (Artists Unknown)

I have to ask: what is there to be proud about? Is Adam Bock formally named as the creator of any part of this memorial? So far as I know, only on the above postcards. The fountain at Tompkins Square Park was sculpted by Bruno Louis Zimm. In The Historical Marker Database, none of the artists for the Middle Village Memorial are mentioned, though a description of the above two statues is given: “To the left and right sides of the Slocum Memorial are smaller monuments: an angel with trumpet, left, and an angel with small child, right. Both have the same inscription that reads, in part, Dedicated to the Organization of General Slocum Survivors in Memory of Their Dead.” I have proof that Adam created those statues (with help). So, perhaps I could be proud that someone in my family contributed to this memorial, helping us to remember “the deadliest disaster in New York before 9/11”? I don’t think so.

The fountain at Tompkins Square Park (Flushing, NY), sculpted by Bruno Louis Zimm.

Who knows about this memorial today? Who knows about the disaster that inspired the memorial? Who cares? “Most of us undoubtedly believe that the Sept. 11 disaster will never be forgotten,” writes Clyde Haberman. “But,” he continues, “the ignored memorials to the General Slocum whisper notes of caution that memory can be faithless” (The New York Times). Are either memorials (the fountain at Tompkins Square Park and the larger memorial in the church cemetery in Middle Village) visited much today? Nope. According to Ranajit Dam, The Triangle Shirtwaist fire (1911) took the Slocum Disaster’s place in prominence; however, the probable real reason why this disaster was mostly forgotten was because all the passengers were German immigrants. “With the two world wars, the ill-feeling toward Germans grew, thereby causing the Slocum disaster to be almost wiped from public memory” (Queens Chronicle). Who would want to remember the tragic accidental deaths of just over a thousand immigrants from an historically aggressively evil country, even if they arrived before World War I, even if many of them were children? Germans immigrated to the United States in the latter part of the 19th Century (the late 1800s). Huge numbers settled in New York. Others moved out westward, such as into the Great Lakes region (Buffalo, Cleveland, Chicago, Milwaukee). When World War I (1914-1918) ended, Germany was blamed (rightly so) for starting the war. When World War II (1939-1945) ended, Germany was again blamed (rightly so) for being a major instigator of that war—as well as for the murdering of millions of Jews and other “undesirable” human beings. Germans who had come to live in the United States had to work hard to distance themselves from their former home country. I remember my grandmother telling me, on numerous occasions in the 1970s, “We aren’t German. We’re American, now. We’ve been in this country since 1905. We had nothing to do with the killing of the Jews.” So, I think it’s understandable why ethically conscious German Americans quieted down about their heritage, their national identity, much less anything tragic that happened to them as a community.

And yet my family has clung to this history, taken pride in it, passed around copies of the postcards. Why? I don’t ask why because of the Germanic heritage issue. I ask why because this just doesn’t seem to be actually much of an accomplishment. Alice Walker points out, “How was the creativity of the black woman kept alive, year after year and century after century, when for most of the years black people have been in America, it was a punishable crime for a black person to read or write? And the freedom to paint, to sculpt, to expand the mind with action did not exist” (“In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens”). Adam was born in Germany. His wife, my great grandmother, Lena, was also born in Germany. Together, they had nine children (two boys, five girls), all born in Germany. My grandmother (Helene) was the youngest, the baby of the family. (She was born in 1900.) They lived in a large house and they had servants. My grandmother used to fondly recall herself, as a very little girl, “going down to the kitchen” where, if she behaved cutely enough, “the cooks” (my emphasis) would give her bits of sausage and other yummy foods. They were wealthy, members of the upper class. They owned a quarry of pink marble. Moreover, Adam was a baron (a member of the nobility: ranking higher than a lord or knight, lower than a viscount or count). Obviously, they lived a life of leisure. Adam had all the advantages that most white people and people of color in the United States did not have. Adam had all the advantages that most women in the United States did not have. Adam even had the advantages that most people with disabilities did not have (note: he became deaf; see below). By that measurement, Adam didn’t accomplish much. Furthermore, from the stories I’ve heard, Adam Bock was hilariously arrogant and pitifully eccentric.

One time, for example, a young man began to visit Adam in his art studio, to study under him. He kept asking Adam all sorts of questions about sculpturing. Adam should have been flattered by this. How honorable it must have been that someone would be so very interested in his work! However, Adam got so annoyed that he said to the young man something like, “Look kid: I appreciate your interest, but you’re a pest. Go away and don’t return.” A few weeks later, he received a letter that was sealed and signed by one of the princes of Prussia, apologizing for being “a pest”. Is this story true? I don’t know. I doubt it. (The only royalty of Prussia alive in that period was Wilhelm II.) To me, the “truth” in this story is that it shows what an asshole my great grandfather was capable of being. Apparently, he was very ashamed of himself, so perhaps he learned his lesson. It doesn’t matter: he had a privileged life.

How Adam and his family came to the United States demonstrates how privileged upper class white men truly were (still are), even when their financial luck runs out. The short of it is this: Adam was standing under a tree during a thunderstorm, when lightening struck the tree (or him, or both him and the tree—I’m not sure). He became deaf, and he went a little insane. (Remember: I mentioned above that he was pitifully eccentric.) The sudden loss of his hearing drove him to spend lots of money traveling all over Europe to find a cure for his deafness. While he was away, according to the family story, an “evil shyster partner” drove the family quarry business into the ground. The family became broke, completely. However, Adam’s sister, Karoline, was married to an American artist, Henry Linder, who (by the way) came to Germany to study under Adam Bock and Karoline’s father, who was actually a well established sculptor in the late 1800s. Connections. Privilege. Henry helped the entire Bock family move to Brooklyn, New York in 1905 (a year after the General Slocum ship sank). My grandmother turned 5 years old on the boat over, and she went from person to person on the ship, saying “Heute ist meine Geburtstag!” (Today is my birthday!”), and people gave her little presents (oranges, chocolate)—she used to tell me that she “made out like a bandit” on that day. Entitlement. Anyway, the family arrived in Brooklyn, and Adam set up a tombstone business.

This building used to house St. Mark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church, whose congregation sponsored the boat excursion on the General Slocum steamer on June 15, 1904. Over a thousand people, mostly women and children, died that day. In 1940, thirteen Jewish women purchased the building, and today it stands as the Sixth Street Community Synagogue/Max D. Raiskin Center.

(SOURCE: “What’s Left of Little Germany in NYC, Kleindeutschland“)

Alice Walker asks, “What did it mean for a black woman to be an artist in our grandmothers’ time? In our great-grandmothers’ day? It is a question with an answer cruel enough to stop the blood” (“In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens”). Walker was born in 1944; she’s roughly of my mother’s generation, which would make her grandmother of my great grandmother’s generation (roughly the same age as Adam and his wife, Lina). In the days of Alice Walker’s grandmother—the same as my great grandmother’s days—no women even had the right to vote in America. But white women still had it better than women of color, and upper class white men had it best of all. Adam’s life, especially before he lost all his money, was extremely privileged, but even after he lost all his money, he still had the connections and support—including the entitlement of an upper class white man—to survive. Because of their family connections in Germany, Adam’s sister (Karoline) met and married an American (see above). They were connected and entitled: upper class white people helping upper class white people. It didn’t even matter that Adam had become so deaf that he couldn’t learn English. (His son, Paul, learned English for the both of them and then would either speak in German so that his father could lip-read him or else write in German on paper.) Adam had the connection to the American, who had some money and his own connections to sponsor the family’s travel to the U.S. and set up a tombstone business. If he hadn’t had those connections, that support, Adam would not have found himself being hired to help create part of that monument.

Moreover, Adam had his wife and numerous children to help bring money into their household. He got to keep being an artist (a tombstone maker, mostly, but an artist nevertheless)! My great grandmother, Lina, took in laundry and sewing jobs. The older sisters (Emma, Margaret, and Elisabeth, all teenagers when they arrived in  Brooklyn) helped with the laundry and sewing jobs. “Everyone had duties,” my grandmother used to tell me: she and the second youngest child, Klara, were still little children, and each had after-school chores to do. These duties were not equitable. The women scrubbed clothes and sewed. Sewing machines existed by then, but they weren’t electric, and “washing machines” were women’s arms and hands. The two brothers (Paul and Oswald) helped their father; they were also artists/tombstone makers. When did any of the family women have time to do art, to carve sculptures out of stone (much less to learn how)? Only the men had that opportunity.

Brooklyn) helped with the laundry and sewing jobs. “Everyone had duties,” my grandmother used to tell me: she and the second youngest child, Klara, were still little children, and each had after-school chores to do. These duties were not equitable. The women scrubbed clothes and sewed. Sewing machines existed by then, but they weren’t electric, and “washing machines” were women’s arms and hands. The two brothers (Paul and Oswald) helped their father; they were also artists/tombstone makers. When did any of the family women have time to do art, to carve sculptures out of stone (much less to learn how)? Only the men had that opportunity.

NOT my grandmother!

And yet, compared to Alice Walker’s grandmother and mother, the “girls” in Adam’s family were still much more fortunate. They also benefited from those upper class white male connections. My grandmother growing up in Brooklyn in the early 1900s had far more opportunities and privileges than Alice Walker had growing up down South a generation later. The Bock Family lived in what was known as “Little Germany” and even though there wasn’t much money flowing around, there were still many connections kept, and new ones being made. How else could it have been that one of the two sons, as well as the three younger daughters, eventually got to go to college? In the 1920s, very few people, much less women, went to college, and the vast majority of them were white. My grandmother graduated from the Pratt Institute (with a degree in Fashion Design) in 1924. With this degree, and some connections, she got a job with Lord & Taylor. When she wasn’t designing clothes, she painted and went to parties.

I can’t help but wonder: how many non-upper-class-white-male and non-upper-class-white-female artists have been lost to us? I’m not trying to shame my family. I don’t hate my great grandfather. I didn’t even know him! I loved my grandmother, used to look up to her—though I can’t picture her in a flapper dress at parties. I can’t help but feel a little family pride: those postcards are displayed in a little glass frame on a shelf in my living room. However, to me, this upper-class-white-male privilege changes the value of art. Should it be singled out as art? Shouldn’t we consider the amount of sheer dumb luck that is involved in becoming an established artist? I try to imagine my great grandmother, Lina, after completing her laundry, sewing, and household chores for the day, sneaking into the studio and working on the statues when Adam and the boys weren’t around. What if Alice Walker’s grandmother could have carved better statues than Adam? The tragedy is that we’ll never know.

How to Cite this Work:

APA Style (missing proper indentation)

Robinson, C. L. (2022, Feb 12). What is an artist, REALLY? College Writing I Reading to Think Lesson R5: Special Topic—Art, Monuments and Memory. https://cyberspacerobinson.org/courses/writing/college-writing-1/course-lessons/reading-to-think-lesson-r4-memory-and-monumental-art/what-is-an-artist-really/